International Bureau of Weights and Measures

| Bureau International des Poids et Mesures | |

| |

Pavillon de Breteuil in 2017 | |

| Abbreviation | BIPM (from French name) |

|---|---|

| Formation | 20 May 1875 |

| Type | Intergovernmental |

| Location |

|

| Coordinates | 48°49′45.55″N 2°13′12.64″E / 48.8293194°N 2.2201778°E |

Region served | Worldwide |

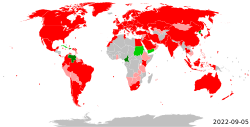

| Membership | 64 member states 37 associate states (see the list) |

Official language | French and English |

Director | Martin Milton |

| Website | www |

The International Bureau of Weights and Measures (French: Bureau International des Poids et Mesures, BIPM) is an intergovernmental organisation, through which its 64 member-states act on measurement standards in areas including chemistry, ionising radiation, physical metrology, as well as the International System of Units (SI) and Coordinated Universal Time (UTC).[1][2] It is based in Saint-Cloud, near Paris, France. The organisation has been referred to as IBWM (from its name in English) in older literature.[note 1]

Structure

[edit]The BIPM is overseen by the International Committee for Weights and Measures (French: Comité international des poids et mesures, CIPM), a committee of eighteen members that meet normally in two sessions per year,[4] which is in turn overseen by the General Conference on Weights and Measures (French: Conférence générale des poids et mesures, CGPM) that meets in Paris usually once every four years, consisting of delegates of the governments of the Member States[5][6] and observers from the Associates of the CGPM. These organs are also commonly referred to by their French initialisms.

History

[edit]After the French Revolution, Napoleonic Wars led to the adoption of the metre in Latin America following independence of Brazil and Hispanic America, while the American Revolution prompted the foundation of the Survey of the Coast in 1807 and the creation of the Office of Standard Weights and Measures in 1830. During the mid-19th century, following the defeat and expulsion of Napoleon Bonaparte's forces which brought an end to the short-lived French occupation of Lower Egypt, the metre was adopted in Khedivate of Egypt an autonomous tributary state of the Ottoman Empire for the cadastre work.[7][8][9] In continental Europe, metrication and a better standardisation of units of measurement respectively followed the successive fall of First French Empire in 1815 and Second French Empire defeated in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871). Napoleonic Wars fostered German nationalism which later led to unification of Germany in 1871. Meanwhile most European countries had adopted the metre. The 1870s marked the beginning of the Technological Revolution a period in which German Empire would challenge Britain as the foremost industrial nation in Europe. This was accompanied by development in cartography which was a prerequisite for both military operations and the creation of the infrastructures needed for industrial development such as railways. During the process of unification of Germany, geodesists called for the establishment of an International Bureau for Weights and Measures in Europe.[10][11]

The intimate relationships that necessarily existed between metrology and geodesy explain that the International Association of Geodesy, founded to combine the geodetic operations of different countries, in order to reach a new and more exact determination of the shape and dimensions of the Globe, prompted the project of reforming the foundations of the metric system, while expanding it and making it international. Not, as it was mistakenly assumed for a certain time, that the Association had the unscientific thought of modifying the length of the metre, in order to conform exactly to its historical definition according to the new values that would be found for the terrestrial meridian. But, busy combining the arcs measured in the different countries and connecting the neighbouring triangulations, geodesists encountered, as one of the main difficulties, the unfortunate uncertainty which reigned over the equations of the units of length used. Adolphe Hirsch, General Baeyer and Colonel Ibáñez decided, in order to make all the standards comparable, to propose to the Association to choose the metre for geodetic unit, and to create an international prototype metre differing as little as possible from the mètre des Archives.[12]

In 1867 at the second General Conference of the International Association of Geodesy held in Berlin, the question of an international standard unit of length was discussed in order to combine the measurements made in different countries to determine the size and shape of the Earth.[13][14] According to a preliminary proposal made in Neuchâtel the precedent year,[15][13] the General Conference recommended the adoption of the metre in replacement of the toise of Bessel,[14][16] the creation of an International Metre Commission, and the foundation of a World institute for the comparison of geodetic standards, the first step towards the creation of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures.[15][13]

Ferdinand Rudolph Hassler's metrological and geodetic work also had a favourable response in Russia.[17][18] In 1869, the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences sent to the French Academy of Sciences a report drafted by Otto Wilhelm von Struve, Heinrich von Wild, and Moritz von Jacobi, whose theorem has long supported the assumption of an ellipsoid with three unequal axes for the figure of the Earth, inviting his French counterpart to undertake joint action to ensure the universal use of the metric system in all scientific work.[19][20] The French Academy of Sciences and the Bureau des Longitudes in Paris drew the attention of the French government to this issue. In November 1869, Napoleon III issued invitations to join the International Metre Commission.[21]

The French government gave practical support to the creation of an International Metre Commission, which met in Paris in 1870 and again in 1872 with the participation of about thirty countries.[22][23] There was much discussion within this Commission, considering the opportunity either to keep as definitive the units represented by the standards of the Archives, or to return to the primitive definitions, and to correct the units to bring them closer to them. Since its origin, the metre has kept a double definition; it is both the ten-millionth part of the quarter meridian and the length represented by the Mètre des Archives. The first is historical, the second is metrological. The first solution prevailed, in accordance with common sense and in accordance with the advice of the French Academy of Sciences. Abandoning the values represented by the standards, would have consecrated an extremely dangerous principle, that of the change of units to any progress of measurements; the Metric System would be perpetually threatened with change, that is to say with ruin. Thus the Commission called for the creation of a new international prototype metre which length would be as close as possible to that of the Mètre des Archives and the arrangement of a system where national standards could be compared with it.[24]

On 6 May 1873 during the 6th session of the French section of the Metre Commission, Henri Étienne Sainte-Claire Deville cast a 20-kilogram platinum-iridium ingot from Matthey in his laboratory at the École normale supérieure (Paris). On 13 May 1874, 250 kilograms of platinum-iridium to be used for several national prototypes of the metre was cast at the Conservatoire national des arts et métiers.[25] When a conflict broke out regarding the presence of impurities in the metre-alloy of 1874, a member of the Preparatory Committee since 1870 and president of the Permanent Committee of the International Metre Commission, Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero intervened with the French Academy of Sciences to rally France to the project to create an International Bureau of Weights and Measures equipped with the scientific means necessary to redefine the units of the metric system according to the progress of sciences.[26][27]

The Metre Convention was signed on 20 May 1875 in Paris and the International Bureau of Weights and Measures was created under the supervision of the International Committee for Weights and Measures. At the session on 12 October 1872 of the Permanent Committee of the International Metre Commission, which was to become the International Committee for Weights and Measures,[28] Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero had been elected president.[29][30] His presidency was confirmed at the first meeting of the International Committee for Weights and Measures, on 19 April 1875.[31] Three other members of the committee, the German astronomer, Wilhelm Julius Foerster, director of the Berlin Observatory and director of the German Weights and Measures Service,[32] the Swiss meteorologist and physicist, Heinrich von Wild representing Russia,[33] and the Swiss geodesist of German origin, Adolphe Hirsch were also among the main architects of the Metre Convention.[28] In the 1870s, German Empire played a pivotal role in the unification of the metric system through the European Arc Measurement but its overwhelming influence was mitigated by that of neutral states. While the German astronomer Wilhelm Julius Foerster along with the Russian and Austrian representatives boycotted the Permanent Committee of the International Metre Commission in order to prompt the reunion of the Diplomatic Conference of the Metre and to promote the foundation of a permanent International Bureau of Weights and Measures,[33] Adolphe Hirsch, delegate of Switzerland at this Diplomatic Conference in 1875, conformed to the opinion of Italy and Spain to create, in spite of French reluctance, the International Bureau of Weights and Measures in France as a permanent institution at the disadvantage of the Conservatoire national des arts et métiers.[34][35]

In 1883, at its seventh General Conference in Rome, the International Geodetic Association would also consider the choice of an international prime meridian and would propose the Greenwich meridian hoping that Great Britain might respond in favour of the unification of weights and measures, by adhering to the Metre Convention.[36]

In recognition of France's role in designing the metric system, the BIPM is based in Sèvres, just outside Paris. However, as an international organisation, the BIPM is under the ultimate control of a diplomatic conference, the Conférence générale des poids et mesures (CGPM) rather than the French government.[37][38] The BIPM was created on 20 May 1875, following the signing of the Metre Convention, a treaty among 17 Member States. As of December 2024, there are now 64 members.[39]

It is based at the Pavillon de Breteuil in Saint-Cloud, France, a 4.35 ha (10.7-acre) site (originally 2.52 ha or 6.2 acres)[40] granted to the Bureau by the French Government in 1876. Since 1969 the site has been considered international territory, and the BIPM has all the rights and privileges accorded to an intergovernmental organisation.[41] This status was further clarified by the French decree No 70-820 of 9 September 1970.[40]

Several significant changes to the BIPM have been made throughout its history during the meetings overseen by the CGPM. An example of this would be how in the 12th general council meeting (held in 1964), the BIPM's budget was increased from $300,000 to $600,000 per year.[42] A historic moment for the BIPM occurred during the 26th CGPM in 2018. At this council, it was decided that world standard for the units of kilograms, seconds, amperes, Kelvins, moles, candelas, and meters would be redefined to reflect constants in nature. This is the first time this has happened since the creation of the BIPM. These changes were made official on World Metrology Day in 2019.[43]

Beginning in 1970, the BIPM began publishing the SI Brochure, a document detailing an up-to-date version of the International System of Units.[44] As of December 2024, the most recent version of the SI Brochure was the 9th edition published in 2019.[45]

Function

[edit]The BIPM has the mandate to provide the basis for a single, coherent system of measurements throughout the world, traceable to the International System of Units (SI). This task takes many forms, from direct dissemination of units to coordination through international comparisons of national measurement standards (as in electricity and ionising radiation).[citation needed]

Following consultation, a draft version of the BIPM Work Programme is presented at each meeting of the General Conference for consideration with the BIPM budget. The final programme of work is determined by the CIPM in accordance with the budget agreed to by the CGPM.[citation needed]

Currently, the BIPM's main work includes:[44][46][47]

- Making brochures that define the International System of Units.

- Scientific and technical activities carried out in its four departments: chemistry, ionising radiation, physical metrology, and time

- Liaison and coordination work, including providing the secretariat for the CIPM Consultative Committees and some of their Working Groups and for the CIPM MRA, and providing institutional liaison with the other bodies supporting the international quality infrastructure and other international bodies

- Capacity building and knowledge transfer programs to increase the effectiveness within the worldwide metrology community of those Member State and Associates with emerging metrology systems

- A resource centre providing a database and publications for international metrology

The BIPM is one of the twelve member organisations of the International Network on Quality Infrastructure (INetQI), which promotes and implements QI activities in metrology, accreditation, standardisation and conformity assessment.[48]

The BIPM has an important role in maintaining accurate worldwide time of day. It combines, analyses, and averages the official atomic time standards of member nations around the world to create a single, official Coordinated Universal Time (UTC).[49]

Directors

[edit]

Since its establishment, the directors of the BIPM have been:[50][51]

| Name | Country | Mandate | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gilbert Govi | Italy | 1875–1877 | |

| J. Pernet | Switzerland | 1877–1879 | Acting director |

| Ole Jacob Broch | Norway | 1879–1889 | |

| J.-René Benoît | France | 1889–1915 | |

| Charles Édouard Guillaume | Switzerland | 1915–1936 | |

| Albert Pérard | France | 1936–1951 | |

| Charles Volet | Switzerland | 1951–1961 | |

| Jean Terrien | France | 1962–1977 | |

| Pierre Giacomo | France | 1978–1988 | |

| Terry J. Quinn | United Kingdom | 1988–2003 | Honorary director |

| Andrew J. Wallard | United Kingdom | 2004–2010 | Honorary director |

| Michael Kühne | Germany | 2011–2012 | |

| Martin J. T. Milton | United Kingdom | 2013–present |

See also

[edit]- History of the metre

- Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements

- International Organization for Standardization

- Metrologia

- National Institute of Standards and Technology

- Seconds pendulum

- World Metrology Day

- Versailles project on advanced materials and standards

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Staff writer (2024). "Bureau international des poids et mesures (BIPM)". UIA Global Civil Society Database. uia.org. Brussels, Belgium: Union of International Associations. Yearbook of International Organizations Online. Retrieved 1 February 2025.

- ^ "Welcome". BIPM. Retrieved 4 March 2024.

- ^ "5 FAH-3 H-310 Organization acronyms". Foreign Affairs Manual. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ "International Committee for Weights and Measures (CIPM)". BIPM. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ Pellet, Alain (2009). Droit international public. LGDJ. p. 574. ISBN 978-2-275-02390-8.

- ^ Schermers, Henry G.; Blokker, Niels M. (2018). International Institutional Law. Brill. pp. 302–303. ISBN 978-90-04-38165-0.

- ^ Jamʻīyah al-Jughrāfīyah al-Miṣrīyah (1876). Bulletin de la Société de géographie d'Égypte. University of Michigan. [Le Caire]. pp. 6–16.

- ^ Ismāʿīl-Afandī Muṣṭafá (1886). Notes biographiques de S.E. Mahmoud Pacha el Falaki (l'astronome), par Ismail-Bey Moustapha et le colonel Moktar-Bey. pp. 10–11.

- ^ Ismāʿīl-Afandī Muṣṭafá (1864). Recherche des coefficients de dilatation et étalonnage de l'appareil à mesurer les bases géodésiques appartenant au gouvernement égyptien / par Ismaïl-Effendi-Moustapha, ...

- ^ Alder, Ken; Devillers-Argouarc'h, Martine (2015). Mesurer le monde: l'incroyable histoire de l'invention du mètre. Libres Champs. Paris: Flammarion. pp. 499–520. ISBN 978-2-08-130761-2.

- ^ Bericht über die Verhandlungen der vom 30. September bis 7. October 1867 zu BERLIN abgehaltenen allgemeinen Conferenz der Europäischen Gradmessung (PDF) (in German). Berlin: Central-Bureau der Europäischen Gradmessung. 1868. pp. 123–134.

- ^ commission, Internationale Erdmessung Permanente (1892). Comptes-rendus des séances de la Commission permanente de l'Association géodésique internationale réunie à Florence du 8 au 17 octobre 1891 (in French). De Gruyter, Incorporated. pp. 99–107. ISBN 978-3-11-128691-4.

- ^ a b c Hirsch, Adolphe (1891). "Don Carlos Ibanez (1825–1891)" (PDF). Bureau International des Poids et Mesures. pp. 4, 8. Retrieved 22 May 2017.

- ^ a b Hirsch, Adolphe. "Procès-verbaux de la Conférence géodésique internationale pour la mesure des degrés en Europe, réunie à Berlin du 30 septembre au 7 octobre 1867". HathiTrust (in French). p. 22. Retrieved 3 February 2025.

- ^ a b Guillaume, Charles-Édouard (1927). La Création du Bureau International des Poids et Mesures et son Œuvre [The creation of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures and its work]. Paris: Gauthier-Villars. p. 321.

- ^ Levallois, J. J. (1 September 1980). "Notice historique". Bulletin géodésique (in French). 54 (3): 248–313. Bibcode:1980BGeod..54..248L. doi:10.1007/BF02521470. ISSN 1432-1394. S2CID 198204435.

- ^ Parr, Albert C. (1 April 2006). "A Tale About the First Weights and Measures Intercomparison in the United States in 1832". Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standards and Technology. 111 (1): 31–32, 36. doi:10.6028/jres.111.003. PMC 4654608. PMID 27274915 – via NIST.

- ^ Cajori, Florian (1921). "Swiss Geodesy and the United States Coast Survey". The Scientific Monthly. 13 (2): 117–129. Bibcode:1921SciMo..13..117C. ISSN 0096-3771.

- ^ Guillaume, Ed. (1 January 1916). "Le Systeme Metrique est-il en Peril?". L'Astronomie. 30: 244–245. Bibcode:1916LAstr..30..242G. ISSN 0004-6302.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 801–813.

- ^ "History – The BIPM 150". Retrieved 24 January 2025.

- ^ The International Metre Commission (1870–1872). International Bureau of Weights and Measures. Retrieved 15 August 2010.

- ^ "History – The BIPM 150". Retrieved 24 January 2025.

- ^ Guillaume, Ed. (1 January 1916). "Le Systeme Metrique est-il en Peril?". L'Astronomie. 30: 242–249. Bibcode:1916LAstr..30..242G. ISSN 0004-6302.

- ^ "History – The BIPM 150". Retrieved 24 January 2025.

- ^ Pérard, Albert (1957). "Carlos Ibáñez e Ibáñez de Ibero (14 avril 1825 – 29 janvier 1891), par Albert Pérard (inauguration d'un monument élevé à sa mémoire)" (PDF). Institut de France – Académie des sciences. pp. 26–28.

- ^ Quinn, T. J. (2012). From artefacts to atoms: the BIPM and the search for ultimate measurement standards. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 9, 11, 20, 37–38, 91–92, 70–72, 114–117, 144–147, 8. ISBN 978-0-19-990991-9. OCLC 861693071.

- ^ a b Débarbat, Suzanne; Quinn, Terry (1 January 2019). "Les origines du système métrique en France et la Convention du mètre de 1875, qui a ouvert la voie au Système international d'unités et à sa révision de 2018". Comptes Rendus Physique. The new International System of Units / Le nouveau Système international d’unités. 20 (1): 6–21. Bibcode:2019CRPhy..20....6D. doi:10.1016/j.crhy.2018.12.002. ISSN 1631-0705. S2CID 126724939.

- ^ Procès-verbaux: Commission Internationale du Mètre. Réunions générales de 1872 (in French). Imprim. Nation. 1872. pp. 153–155.

- ^ Torge, W. (1 April 2005). "The International Association of Geodesy 1862 to 1922: from a regional project to an international organization". Journal of Geodesy. 78 (9): 558–568. Bibcode:2005JGeod..78..558T. doi:10.1007/s00190-004-0423-0. ISSN 1432-1394. S2CID 120943411.

- ^ Comité des International Poids et Mesures (1876). Procès-Verbaux des Séance de 1875–1876. Paris: Gauthier-Villars. p. 3.

- ^ Quinn, Terry (May 2019). "Wilhelm Foerster's Role in the Metre Convention of 1875 and in the Early Years of the International Committee for Weights and Measures". Annalen der Physik. 531 (5). Bibcode:2019AnP...53100355Q. doi:10.1002/andp.201800355. ISSN 0003-3804.

- ^ a b Comité Interational des Poids et Mesures. Procès-Verbaux des Séances. Deuxième Série. Tome II. Session de 1903. Paris: Gauthier-Villars. pp. 5–7.

- ^ "Bericht der schweizerischen Delegierten an der internationalen Meterkonferenz an den Bundespräsidenten und Vorsteher des Politischen Departements, J. J. Scherer in Erwin Bucher, Peter Stalder (ed.), Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland, vol. 3, doc. 66, dodis.ch/42045, Bern 1986". Dodis. 30 March 1875.

- ^ Dodis, Diplomatische Dokumente der Schweiz | Documents diplomatiques suisses | Documenti diplomatici svizzeri | Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland | (30 March 1875), Bericht der schweizerischen Delegierten an der internationalen Meterkonferenz an den Bundespräsidenten und Vorsteher des Politischen Departements, J. J. Scherer (in French), Diplomatische Dokumente der Schweiz | Documents diplomatiques suisses | Documenti diplomatici svizzeri | Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland | Dodis, retrieved 20 September 2021

- ^ Hirsch, A; von Oppolzer, T (1884). Comptes rendus des séances de la ... Conférence générale de l'Association géodésique internationale (in French). G. Reimer. p. 202.

- ^ Nelson, Robert A. (December 1981). "Foundations of the international system of units (SI)" (PDF). The Physics Teacher. 19 (9): 596–613. Bibcode:1981PhTea..19..596N. doi:10.1119/1.2340901.

- ^ Article 3, Metre Convention.

- ^ "Member States". BIPM. Retrieved 6 December 2024.

- ^ a b Page, Chester H; Vigoureux, Paul, eds. (20 May 1975). The International Bureau of Weights and Measures 1875–1975: NBS Special Publication 420. Washington, D.C.: National Bureau of Standards. pp. 26–27.

- ^ "History of the Pavillon de Breteuil". BIPM. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ Astin, A. V. (28 February 1964). "Weights and Measures". Science. 143 (3609): 974–976. Bibcode:1964Sci...143..974A. doi:10.1126/science.143.3609.974. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17743934.

- ^ Reed, EMAP: Emily Li, Graham Strzelecki, Maddie Rouse, and Andrew (1 February 2022). "26th General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM)". ArcGIS StoryMaps. Retrieved 31 October 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Wallard, Andrew J. (March 2006). "The International System of Units (SI brochure (EN)): 8th edition, 2006" (PDF).

- ^ "The International System of Units (SI)". Peter C. Burbery website. 20 December 2022. Retrieved 7 November 2024.

- ^ "BIPM: Our work programme". BIPM. Archived from the original on 30 May 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ Cai, Juan (Ada). "The Case of the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (BIPM)" (PDF). oecd.org. OECD. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ "International Network on Quality Infrastructure". INetQI. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ "Time Coordinated Universal Time (UTC)". BIPM. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ "Directors of the BIPM since 1875". Bureau International des Poids et Mesures. 2018. Archived from the original on 27 March 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

- ^ "NPL Fellow, Dr Martin Milton, is new Director at foundation of world's measurement system". QMT News. Quality Manufacturing Today. August 2012. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 14 May 2020.

External links

[edit] Media related to International Bureau of Weights and Measures at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to International Bureau of Weights and Measures at Wikimedia Commons- Official website